On April 4th, the Chinese government made official its response to the tariffs approved by the Donald Trump administration. On April 10th, China will impose a tariff of 34% on all imports from the US. The choice of that day is no coincidence. The tariffs approved by the Donald Trump administration will come into force on April 9th. Just one day earlier.

Presumably the Chinese government has chosen to allow a few days’ leeway in the hope of reaching some kind of agreement with its US counterpart and easing the tension a little. However, China’s response to the US does not only involve establishing new tariffs; it has also chosen to suspend import licenses for products belonging to six US companies, as well as imposing further export controls on some rare earths.

This is by no means the first time that Xi Jinping’s government has decided to put pressure on the US and its allies by placing restrictions on the export of these raw materials. In fact, on December 21, 2023, the Chinese administration decided to restrict the export of some of its rare earth processing technologies, in a maneuver aimed at defending its strategic interests in the midst of confrontation with the US and its allies. And in early December 2024, it opted to ban the export of critical minerals to the nation currently ruled by Donald Trump.

The US is going to run out of scandium and dysprosium from China

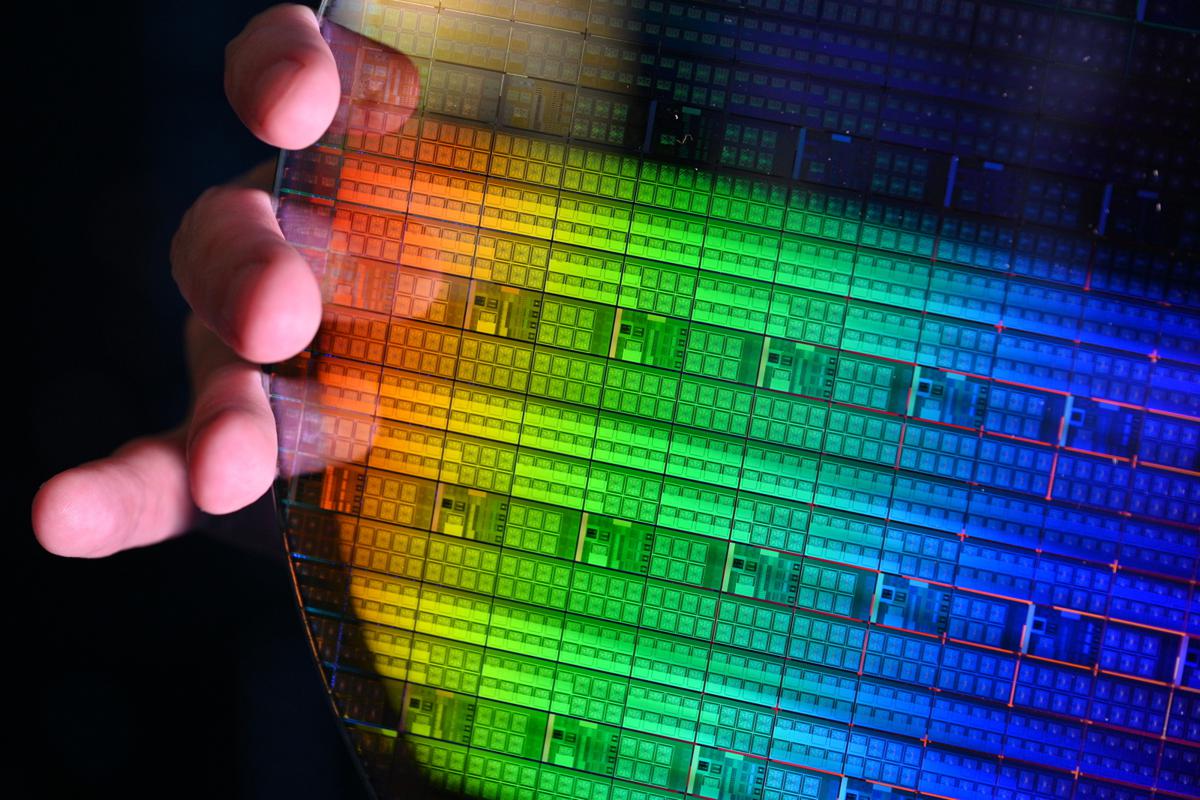

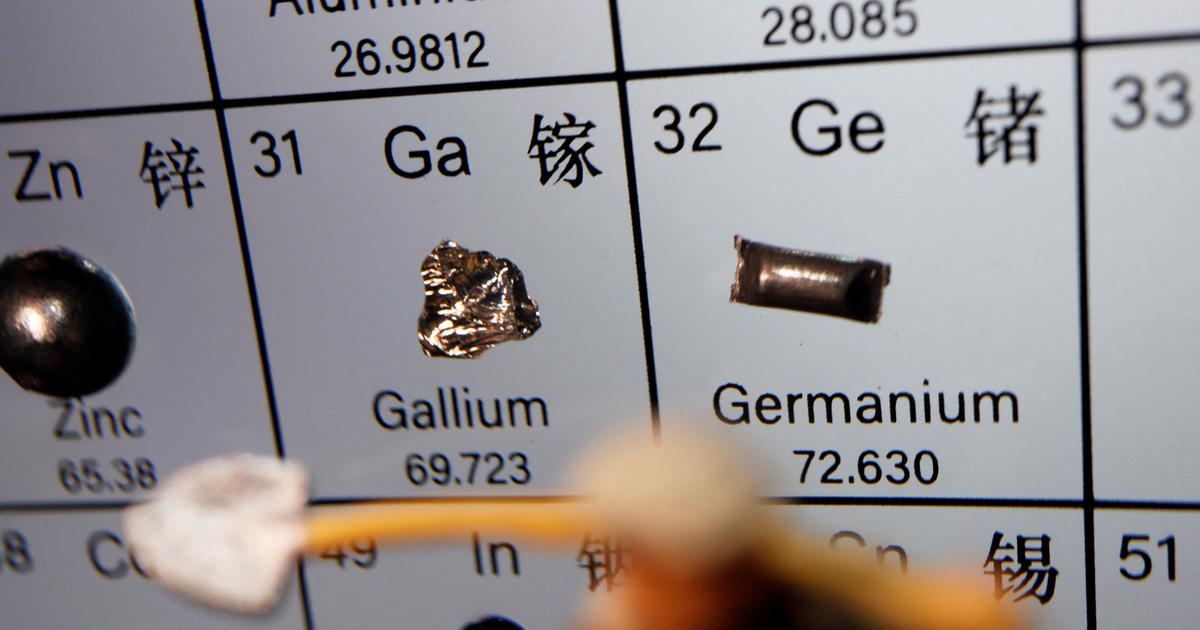

Since last December, China has not exported to the US three chemical elements essential to the semiconductor industry (gallium, germanium and antimony), as well as some materials that are characterized by their extreme hardness, and which, therefore, can be used for military applications. However, in response to the latest tariffs approved by the US, the Chinese government has decided to include scandium and dysprosium in its list of transition metals subject to export controls.

These chemical elements are probably less well known than the metals previously banned by China, such as gallium or germanium, but they are at least as important as the latter. In fact, Xi Jinping’s administration has chosen them because it is fully aware of the profound impact these restrictions will have not only on the telecommunications and storage device manufacturing industries, which they directly affect, but on the entire global supply chain linked to the semiconductor industry.

Scandium is commonly used in the radiofrequency modules used in smartphones, base stations and Wi-Fi modules, while dysprosium is involved in the manufacture of the read and write heads used in hard drives, and also in the manufacture of electric cars. The Ministry of Commerce of China has banned the export of these metals to the US with immediate effect, so Chinese companies can no longer export products containing scandium, dysprosium, gadolinium, terbium, lutetium, samarium and yttrium.

Presumably, export licenses for these critical minerals will only be granted under certain very strict conditions. However, the ban does not only condition the export of finished products containing these metals; it also denies the export of these raw minerals, in the form of metal or as compounds. Some of the companies that are likely to suffer from China’s new bans on critical minerals are American, such as Broadcom, Qualcomm, Seagate and Western Digital. But there are also Taiwanese and South Korean companies, such as TSMC and Samsung. In the short term, global geopolitical tensions do not appear to be abating.